Mapping pangolin trafficking from Africa to Asia

Pangolins are the most trafficked mammals in the world. We’re uncovering where African pangolins are poached and the routes they take to market

Status: Completed

Despite their scaly appearance, pangolins are mammals. These scales evolved to protect pangolins from predators. When they sense danger, they roll up into a ball with their scales facing outward. Although this behavior may sound like armadillos, pangolins belong to their own Order, Pholidota. They diverged from their closest relatives, the carnivores, 62 million years ago. Four species of pangolin are found in Southeast Asia, and another four occur throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

Pangolins are toothless and have evolved long tongues and sticky saliva to help them catch their prey–ants and termites. They frequently specialize in just a few species of ants or termites, which makes them nearly impossible to keep in captivity. Thus, when people consume pangolin products, they come from wild animals. Demand for pangolin products has driven the unsustainable harvest of pangolins in Asia and Africa and threatens these unique mammals with extinction. To protect pangolins, the international trade in pangolin products was banned in 2016.

Pangolins in peril

The globalization of the illegal wildlife trade has made preventing poaching more complex than ever before. China is the largest market for pangolin scales, which are valued for perceived medicinal properties. This demand has led to the over-harvesting of Asian pangolin species. Continued demand and increasing economic ties between Asia and Africa now threaten African pangolins. The complicated web of routes that pangolins take from forests in Africa to markets in Southeast Asia have been nearly impossible to trace, and pangolins are being trafficked in greater numbers than ever before.

Nearly 200,000 trafficked pangolins were seized by customs officials in the first half of 2019. That’s more than were seized in all of 2018, and up from 10,000 trafficked animals in 2013. These numbers are unsustainable. Unfortunately, confiscations by law enforcement provide only limited information about the sources of trafficked pangolins. Scales from multiple countries in Africa are often amassed at one port before shipment, making it impossible to determine where poaching is actually occurring. Urgent work is needed to identify where these shipments originate, so that law enforcement can stop poaching before it happens.

By mapping pangolin supply chains, we’re giving law enforcement around the world the tools they need to disrupt wildlife trafficking and stop the pangolin crisis.

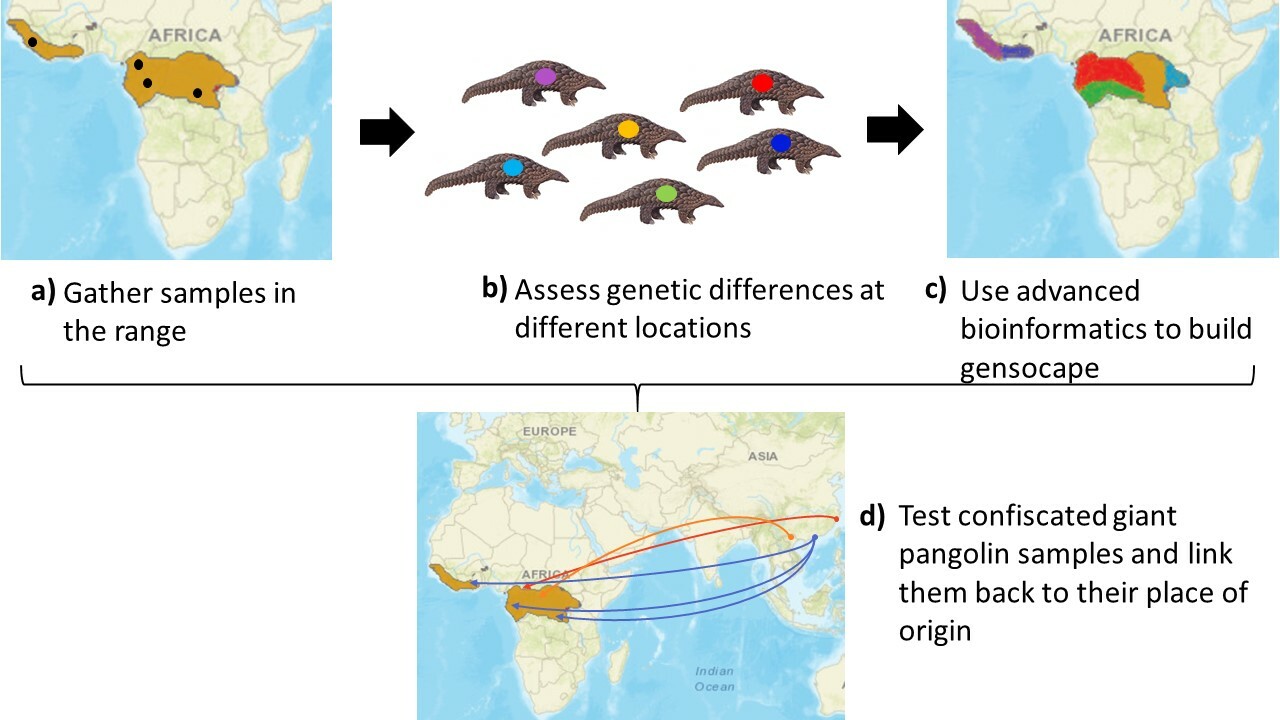

CBI and partners are developing forensic tools to link confiscated pangolin scales to the populations where they originated. To do this, we are mapping genetic variation in wild pangolins, and identifying geographically unique genetic markers. We will use these markers to tell where confiscated scales came from.

Four Steps in Mapping Pangolin Trafficking:

- Collect samples with partners

- Genetically distinguish pangolin populations

- Determine geographic limits of populations

- Link confiscated samples to their origin population

We work with teams of wildlife experts and conservationists to collect samples from pangolins already for sale at local markets. No animals are ever purchased or harmed on behalf of the pangolin project.

CBI has collected georeferenced samples from eight West and Central African countries. We have also partnered with Klaus-Peter Koepfli and his team at the Smithsonian Zoo to develop the most complete genome for any pangolin to date. This genome will help us compare samples from wild pangolins to each other and to identify genetic markers that are unique to different populations and geographic areas. We are also developing a genoscape: a map of genetic differences in pangolins over geographic areas, and the markers that distinguish pangolins from one area from pangolins from a different area. We will use these markers to make a simple test that can determine where confiscated scales originated. This test is critical—it will allow researchers to identify current poaching hotspots. Researchers will be able to update these hotspots as traffickers adapt to law enforcement strategies and change where they hunt pangolins.

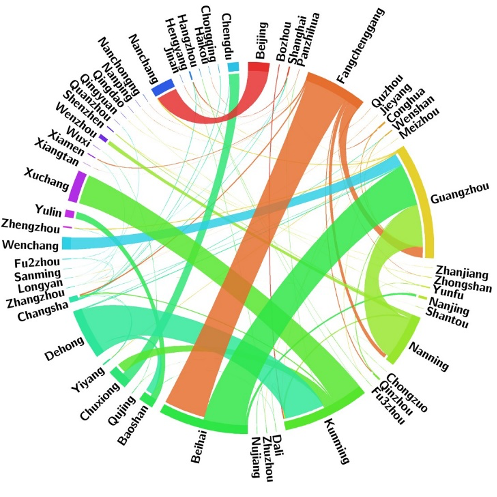

CBI is working with Tim Bonebrake and Caroline Dingle at the University of Hong Kong to identify which markets are driving the import of African pangolins to Southeast Asia and which ports are major trafficking hubs. Combining this network analysis with our genetic data will provide a complete picture of pangolin trafficking from African forests, to major shipping ports, and ultimately to their final market destinations.

We are also working to put these tools in the hands of African stakeholders from the government, scientists, and conservation organizations. CBI has hosted two workshops in Cameroon for policy makers and researchers to familiarize them with these methods and to help them deploy conservation forensics in their poaching prevention efforts. More than sixty attendees from four Central African countries came together to learn and brainstorm ways to help protect pangolins.